\ˌrä-də-mən-ˈtād \

A quick check of the dictionary revealed that a rhodomontade (or as it is more usually spelled, rodomontade) is an extravagantly boastful and bombastic speech. There are certainly plenty of those around these days, but I’ve never heard them called that, and that was excuse enough for muting Twitter for a few minutes and doing some investigation.

Rodomontade, it turns out, is a made up word. It exists in French and Italian, but it does not come from an earlier root—instead it comes from the name of a character in Matteo Maria Bolardo’s hugely popular Orlando Innamorato and Ludovico Ariosto’s even more popular sequel, Orlando Furioso.

These epic poems were written in the late 15th and early 16th century and have inspired countless works over the years, from The Fairie Queene and Much Ado About Nothing to Monty Python and Mad Max: Fury Road. The plot is nearly impossible to summarize but as the title suggests the central character Orlando—a Christian knight during the time of Charlemagne—starts out in love and ends up furious. He falls passionately in love with a lady, and when she runs off with someone else, he goes mad with despair and grief and goes rampaging naked across Europe and Africa, destroying everything in his path. As one does.

But Orlando is not the half of it. His story is tangled up with those of dozens of other characters who go racing in and out of the frame, fighting, falling in love, having visions, being enchanted, making imprudent wagers, and generally trailing plot complications into an impenetrable thicket of preposterous incident. There’s war! Politics! Sex! Woman warriors! Passion! Revenge! Disguises! Mistaken identity! Returns from the dead! Hippogriffs! Voyages to the moon! Whatever you are looking for in a narrative, Orlando has it on offer.

So she insists that carnal congress is not in the cards, but she does offer to brew him a potion that will make him invulnerable to arrow or sword. Rodomonte thinks this sounds like a great idea (plus he is sure he’ll be able to talk her out of the chastity thing later). But she is too clever for him: she brews the potion, gets him drunk, smears the stuff all over her naked body and invites him to prove the potion’s effectiveness by attacking her with his sword—which he does, killing her on the spot. “Neener, neener, still chaste!” her severed head says as it rolls across the floor (or words to that effect).

(I must pause here to observe that while I am no tactical genius, I can think of several ways this young woman might have made more sensible use of the this-guy-is-both-gullible-and-drunk dynamic at work here. Like, oh I don’t know, RUNNING AWAY or GETTING HIM TO STAB HIMSELF NOT HER. This is why I have not been hired to write any 15th century Italian epics.)

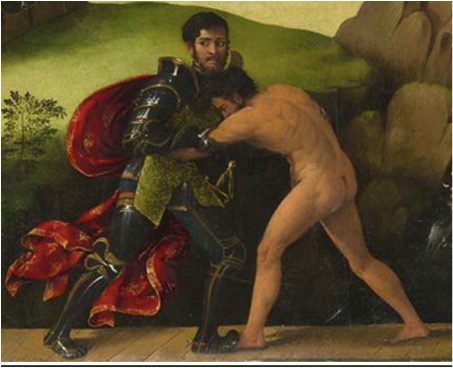

Rodomonte has enough grace to feel kind of bad about the whole thing, so he builds a bridge in the young woman’s memory and camps out on it so he can yell threats at travelers until they give him tribute money. When Orlando at last comes rampaging through this subplot, naked and insane because or course he is, the two have a shouting match on the bridge, which segues into a colossally awkward shirts vs skins wrestling bout, at the end of which both men fall into the river. Orlando climbs out of the water and goes roaring off into the next canto, and Rodomonte, armor aslosh, is left to scramble back up to his bridge and prepare to yell at the next guy.

It occurs to me that Rodomonte and his mountain gnawing are not a bad metaphor for this shouty season. There certainly are plenty of callous would-be generals slinging people into rocks and carrying on about their exploits. But the sheer gonzo exuberance of Orlando reminds me that however loud they yell they are only one thread in the crazy tangle of plots on our plate. If the rodomontades are too much to take, we can put that plot down for a while and follow another thread. Maybe one of the ones with hippogriffs in it.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed