/pī/

There’s a lot of PIE out there. Depending on the context, it can refer to Prince Edward Island, or to pulmonary interstitial emphysema, or to the Principle of Inclusion/Exclusion (which Everett tells me is a formula for counting up the number of objects that are contained in overlapping categories),* and a host of other things.

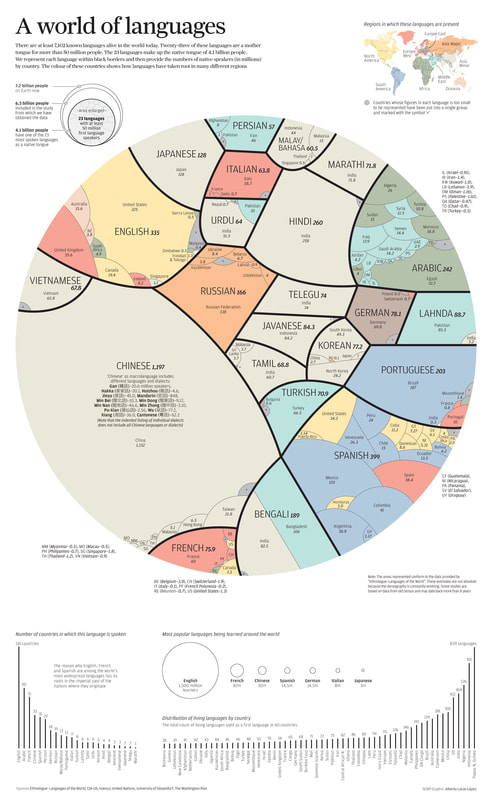

Most of the other half speak Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Malay—a fact beautifully illustrated by an image shared by another Lovely and Intelligent Reader, which presents the world’s major languages according to number of speakers. This is, appropriately enough, termed a pie chart; one might even call it a PIE pie chart, though the largest piece, being Chinese, has no connection to PIE at all.**

| And all-caps levels of enthusiasm are warranted! Pie is in fact one of my favorite foods. It is defined as a sweet or savory dish, usually consisting of meat or fruit cooked in (or sometimes under) a pastry shell. (Dough-less variations like shepherd’s pie notwithstanding, I do think that pastry is essential to pie-ness.) |

| Magpies are pretty great. Like other corvids, they are extremely smart—some scientists say that they are as intelligent as great apes in their grasp of cause and effect, as well as their social intelligence, imagination, and ability to anticipate future events. They use tools, they work in groups to hunt for food and outwit predators, and they can count. |

But I think a more promising vein lies in magpies’ fondness for picking up shiny objects and hoarding them in their nests. There is a French expression, trouver la pie au nid, which means to make an unexpected and pleasant discovery, or literally to “find the magpie in its nest.” And pie, after all, is a collection of often random foodstuffs gathered into a nest-like pastry shell. Think mincemeat, or four-and-twenty blackbirds (which I suppose might be a pie pie***). Still not convinced? Think, then, of haggis, the Scottish dish consisting of a motley assortment of offal, oatmeal, and suet boiled in a sheep’s stomach. The etymology of haggis is unclear, but there is an English word haggess that dates back to the early 13th century. It means—I kid you not!—magpie.

So there is a strong case to be made that pies are called pies because they are unexpected and sometimes disorderly collections of treasures, hidden in a pastry shell or box and waiting for us to discover them, like Jack Horner with his anarchic thumb spearing the Christmas plum.

I like this whiff of chaos within the array of neatly crimped pies in the baker’s window. It reminds me of one of the most joyous and disorderly applications of pie—the pie fight. This is such a classic trope you might think it has been going on for millennia, but no—pie-throwing is apparently a 20th century art form. The first documented instance I can find is in a 1909 film called Mr. Flip. But once the pie had been cast, filmmakers realized that this was comedy gold. Charlie Chaplin had his first pie fight in 1916, and Laurel and Hardy’s The Battle of the Century (1927) is an acknowledged masterpiece of the genre.

| One of my favorite pie fights occurs in The Great Race, featuring Natalie Wood, Jack Lemmon, Peter Falk, Tony Curtis, and about 4,000 pies. Like all great scenes of its kind, one of the most delicious bits occurs at the very beginning, when the protagonists burst through a door—and we see that they have arrived in a room FILLED WITH PIES, row upon neatly stacked row of them, and we know the scene can only unfold in one way. | |

Which brings me back to PIE. One of the joys of playing around with words on this blog is getting a good look at the utter mayhem at work in the English language. There is nothing like the moment of glee I feel when I crack open the OED and see a nice fat etymology entry, a magpie in its nest, stuffed with disputes and detours and weird convergences. Linguists may have figured out a nice tidy protolanguage in PIE, with its tables of inflections and declensions, its conjugations and ablauts. But every time English seems to settle down, along comes something like the Norman Conquest or the Industrial Revolution or emojis, and we are off to the races again. English is a magpie stealing shiny objects for its nest of treasures, a linguistic pie fight that kicks over the table and splatters custard on everyone in range.**** Crimp your crusts all you want, PIE! We’ve got our own pies, and we’re not afraid to fling them.

Splat!!

*He also tells me that it is properly called the Inclusion/Exclusion Principle; however, that would be IEP rather than PIE, so I choose to disregard.

**There may be no Chinese connection to PIE, but there is such a thing as Chinese Pie. Also known as Pâté Chinois, this is a French Canadian variation on shepherd’s pie, consisting of layers of ground beef, sautéed onions, and canned creamed corn, all baked under a mashed potato topping. The story, which might even be true, is that the dish was made by Chinese cooks working on the construction of the trans-Canadian railway. While I can’t imagine Chinese laborers finding this at all appealing, their French Canadian counterparts became quite fond of the stuff and, it being cheap, filling, and easy to make with available ingredients, they brought the recipe home with them. Some now claim Pâté Chinois as the national dish of Québéc.

***OK fine, all you bird pedants, blackbirds aren’t corvids; they are from the thrush family. But many corvids are black birds and the rhyme does not specify the precise taxonomy. I will not retract.

****As professional nerd James Nicholl memorably put it: English doesn’t just borrow words, "English pursues other languages down alleyways to beat them unconscious and rifle their pockets for new vocabulary.” (This quote is often misattributed to the late great Terry Pratchett, but while Sir Terry may well have shared the sentiment, it was Nicholls who actually said it.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed