\ˈstāj\

Making a house we’ve been in for twenty years presentable for sale has been no small task. The last couple of months have been a frenzy of thinning things out and packing things away and delving into corners and deep cabinets and the backs of closets. Extraneous furniture has been sold or stashed in the garage. We’ve schlepped carton upon carton of donations to the Friends of the Library and the church book room. I’m on a first-name basis with the guy at the Goodwill dropoff. (Hi Ramon!) A platoon of tradesmen has come through, painting and pruning and weeding and patching and repairing.

At the end of all that activity we thought things looked pretty good. But no, the realtors told us, that had been but the prelude—it was time to prep the house for showing. It was time to bring in the stagers.

A stage is a raised platform on which something can be built or performed. It is a place where fantasies and dramas are acted out, where illusions are given the gloss of reality. In construction, it can be a scaffold or step, a place from which work can continue at a higher level. The word comes from the Old French estage, which in turn comes from the Latin stāre (meaning to stand); estageis also the source of the modern French étage, meaning a floor in a multistory building.

Staging a house is highly performative. The idea is to present the house in its ideal form, devoid of the personality of its owners, with just enough cues that prospective buyers can visualize themselves inhabiting it. Just as important, the buyer is supposed to imagine the new and improved life they will live in this space: it needs to conjure up not only who they are, but who they can become. That vision is aspirational—it is about leveling up.

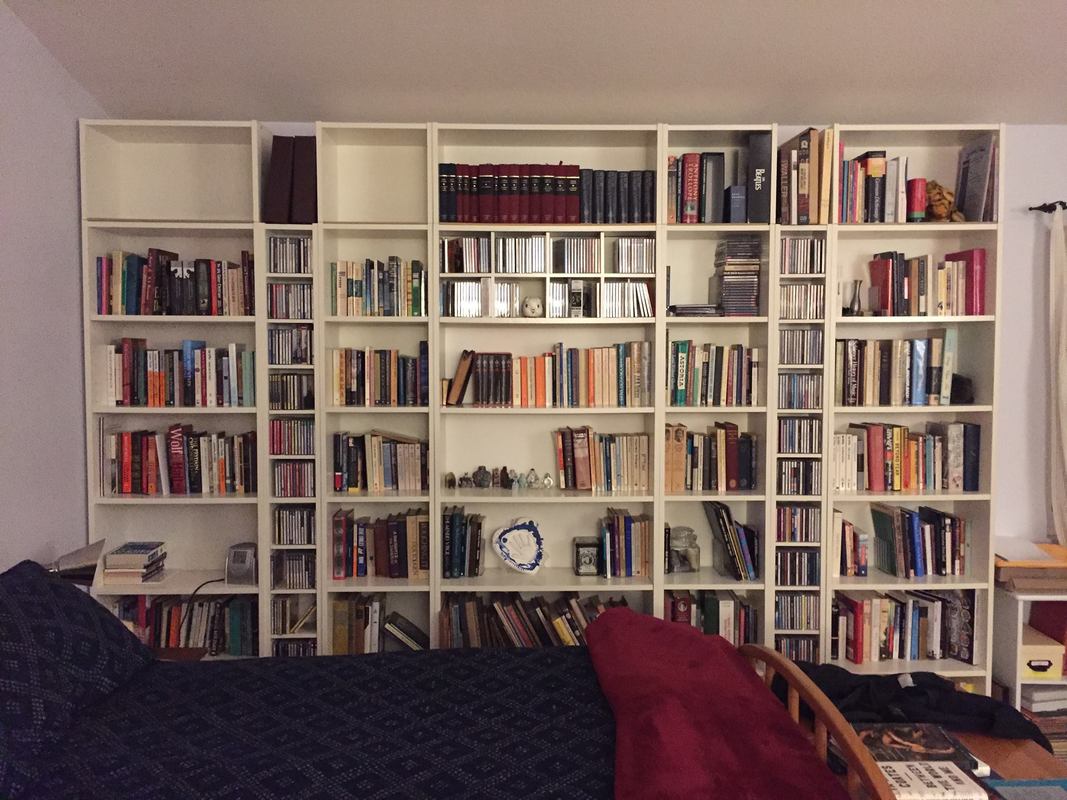

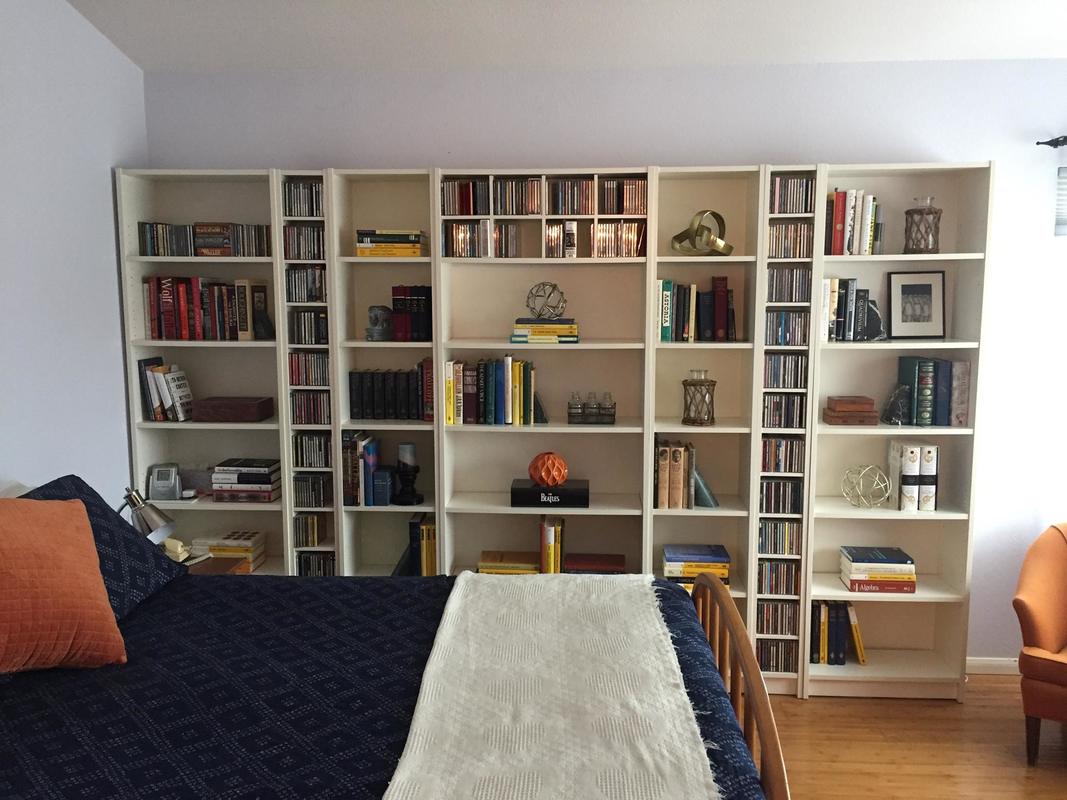

House stagers are expert at invoking that aspirational vision. Consider what they did with our bookshelves. We live in a suburb known for its good public schools. In theory, a house full of books should appeal to upwardly mobile young families looking to settle here. Books say: People who live here are readers! They are informed and erudite! They succeed in their professions and throw interesting dinner parties!

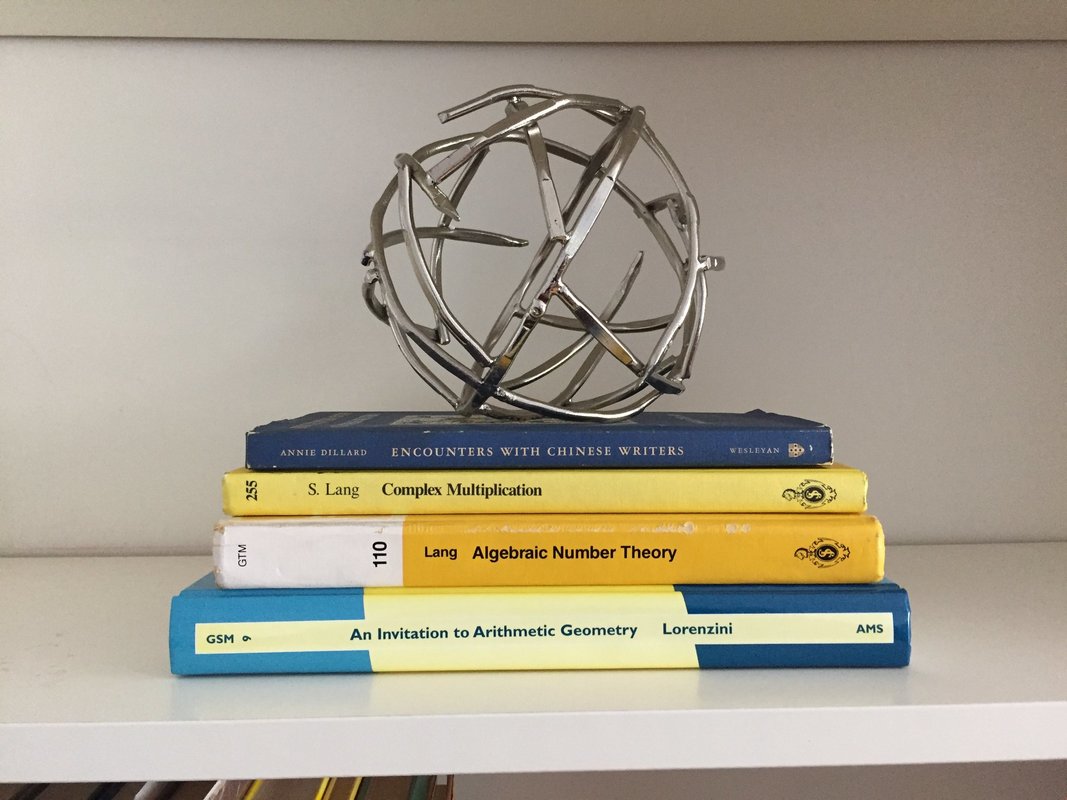

| First, they did another shelf purge. The remaining few books were tastefully grouped with an eye to size, color, and visual weight. A fair number ended up stacked on their sides and crowned with decorative objects. |

The staging of the rest of the house, though, was more upsetting. Here were the artifacts of our lives—our furniture, our pictures, our stuff—polished up and arrayed to present an idealized vision of suburban prosperity straight out of a Pottery Barn catalog. The counter that had for 20 years been the daily repository for groceries and mail and keys and lunchboxes was now a breakfast bar, complete with multi-layered place settings that we were forbidden to touch lest we sully the pristine arrangement of napkin-on-plate-on-larger-plate-on-mat. The landing where we once dumped miscellaneous furniture and the occasional laundry basket was recast as a reading nook. Fake plants and twee knickknacks appeared—raffia spheres in glazed bowls and cunning candleholders made from wrought iron and mason jars. Throw pillows popped up like dandelions.

But the final straw for me was a tasteful little vignette that included a family portrait taken when our kids were in middle school. Suddenly what was on stage was not just our stuff—it was us. Our family was being deployed in the service of an aspirational vision of white, heterosexual, educated, upper-middle-class, happy nuclear family “normality.”

Unsurprisingly, the agents suggested we make ourselves scarce for a few days while they held open houses and walked potential buyers through the property. The last thing they needed was some homeowner barging onto the stage muttering balefully about capitalism and heteronormativity. So we decamped to an Airbnb—and by the time we returned four days later, we had an offer in hand and were embarking on a new stage called escrow. (Which, it turns out, is a rather interesting word in its own right, but I will save it for later.)

Since we got back, the Pottery Barn ideal has been slowly succumbing to the wear and tear of daily life (though we still haven't dared touch the breakfast bar napkins). But I took down the family portrait display. I wasn't sure who those people are any more.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed